Dividends vs. Buybacks – Take My Money, I Didn’t Ask for a Refund

Conventional wisdom is that dividends are great – for many people they are the main reason why people invest in companies in the first place. A dividend is your share of a company’s profits – when the company does well, they pay a dividend to their shareholders.

Within this context, the idea of “share buybacks” seems shady – rather than paying the shareholders their due, the company instead embarks on some back-room market manipulation, spending the shareholders cash to prop up the share price and net the executives a bigger bonus.

This narrative, that share buybacks are done to enrich insiders at the expense of other shareholders, and that dividends are fundamentally different, better, simpler and more honest, is incorrect and unhelpful. It is an overly divisive way of framing a fairly technical choice, that leads people to favour a more obscure system. In this post I hope to offer a viewpoint that explains the following:

- They are basically accomplishing the same thing, but dividends are a more confusing way to do it

- The ways in which they don’t result in the same outcomes are artificial, arising from legislation treating them as though they are not the same

- Any accusations of insider shenanigans can apply equally to either, and many claimed problems with buybacks are complete non-issues

- Buybacks are just better than dividends. As well as being more complicated, dividends reduce choice and possibly encourage short-termism

Keeping People Happy

Given the fact that many consider dividends to be the fundamental reason behind investing in the first place, in order to make an argument about their equivalence to buybacks, we need to dig into a more fundamental concept. What are shares for, and why do we buy them?

A share gives you part-ownership of a business entity. Owning a share means that you own a tiny proportion of everything that makes up the company – its physical assets, its bank accounts, and any future profits or investments it might make. If the company ceased trading and liquidated its assets, once all its creditors had been paid, you would be entitled to a proportion of the remaining money. Of course, this rarely happens outside of corporate bankruptcy, in which the company is in dire straits and cannot afford to pay its creditors, which usually means that there won’t be much left (if anything) for the shareholders once all debts are paid. In principle though, you could wind up a company and liquidate its assets, and it is this value, combined with an expectation of how this value might grow in future that determines what people are willing to pay for a share.

When the stock market was a new idea, it was a wild-west out there. Some companies were just pyramid schemes, relying on a “greater fool” to buy shares from existing shareholders, until some people were left “holding the bag”. With weak regulation, and investors that didn’t have much experience (because no-one had much experience when the stock market was new), companies needed a way to distinguish themselves from pyramid schemes. In this environment, paying dividends gave companies legitimacy. Owning a share that paid regular dividends gave you a demonstrable financial benefit without having to sell the share to someone more gullible.

In modern times, there is a plethora of regulation – companies publish regular financial statements, and securities fraud is treated and policed very seriously. This allows people to have a much greater degree of confidence in the financial status of their investments, reducing the need to demonstrate legitimacy through dividend payments.

Instead of paying dividends, a company with a significant amount of cash in their bank account may of course choose to invest their money in other growth opportunities. This would be done with the aim of increasing the net worth of the company, and therefore increasing the share price. If they do not currently have a suitable investment opportunity however, it would still be in the company’s interest to return this unused cash to the shareholders somehow. This is because sitting on cash is actually expensive for companies.

Burning a Hole in Your Pocket

The last sentence might sound odd. Surely sitting on cash doesn’t cost anything, after all as individuals, many people stash money away in their bank accounts, and this is considered prudent – “saving for a rainy day”. Of course, having a certain amount of cash is useful for companies too – if you can’t pay your employees after a bad month of sales, you aren’t going to be in business long. This desire to have a bit of a cash buffer is very reasonable, but the bigger the buffer you have, the more expensive it is.

The idea that it is expensive to sit on a large cash balance comes down to the idea of “cost of capital”. Banks loaning money to a company charge interest, which provides them with a return on their investment. This interest is referred to as a cost of capital, as it is a cost the company must pay as a result of the capital investment the bank provided. In much the same way, shareholders expect a certain return on their investment – the capital they contribute isn’t free either. In fact, this expected return is usually higher than the return a bank would make on a loan, as the bank is taking a lower risk – they’ll get their money back first if the company goes under.

This means that every pound or dollar of capital a company has is costing them – either in terms of interest to a bank, or expected return to a shareholder. If a company isn’t growing fast enough relative to the amount of capital invested, the share price will fall, and the shareholders will be unhappy. If a company has assets that it isn’t using, they are not contributing to the company’s growth, so their associated cost of capital is just a drag on the business.

The cost of capital forces companies to strive to be as lean as they can reasonably manage – maximising the growth they can achieve whilst minimising the capital they require to achieve it. Whether it is cash languishing in their bank account, or a factory standing idle, these represent an unnecessary cost that can be done away with. This is one of the main reasons why companies return cash to their investors – it reduces their cost basis. The investors can then take this money and invest it elsewhere at a higher rate of return than the company could otherwise have achieved with it.

With this background, we can start to explore the impact of the different ways a company might dispose of its excess cash.

1a. Accomplishing the Same Thing in Different Ways

The obvious way that a company could return cash to its investors is through dividends – just paying a bit of the excess money to each shareholder in proportion to the number of shares they hold.

If a company with a share price of £100 and 1 million shares (therefore a market capitalisation of £100 million) were to have £5 million of cash in excess of what they needed, they could pay a £5 per share dividend. This would reduce its market capitalisation to £95 million, and therefore the share price of all 1 million shares would drop to £95.

Note: because dividends can’t easily be paid to all shareholders instantaneously, a work-around is used. At a particular point in time, rather than paying the dividend itself, it is instead determined who owns the shares and should therefore receive the dividend (the day before the “ex-dividend date”). The payments to these people can then be made over the next few days, regardless of who buys or sells in the meantime.

This share price drop on the ex-dividend date is well documented – it is a result of the stock market being a highly efficient price determination mechanism. After all, if you own something worth £100, that you know has the capability to pay you £5, once it has paid you the £5 it must be worth £5 less. If it were worth £100 both before and after paying the dividend, someone could have bought it from you before the dividend was paid for £101, and sold it back to you after the dividend for £99, and still made a guaranteed £3 profit.

Of course, real life always makes things slightly more complicated – share prices fluctuate all the time, so in the instant a share’s ex-dividend date is reached, a stock might drop more or less than the value of the dividend, because other factors affecting the share price are also contributing to the movement.

Another way that a company could return cash to its investors however is through a share buyback – the company could use its cash to buy shares on the open market (or from shareholders directly), reducing the number of shares in circulation.

If the company above were to use its excess cash to perform a share buyback, instead of paying a dividend, it would still have £5 million of cash to pay out, which would therefore still reduce its market capitalisation to £95 million. Rather than paying an amount to every shareholder, thereby reducing the value of each share, it would instead simply buy 50,000 of its own shares, reducing the total number of shares in circulation to 950,000. Each share would therefore still be worth £100 to all of the shareholders that didn’t sell.

Under this approach, even if the market for the stock isn’t particularly liquid (i.e. the number of buyers and sellers is low, meaning that if you wanted to sell, you might have to wait some time, or accept a lower price in order to sell quickly), the company can periodically buy people out of their shareholdings. People can rely on the company itself to be the “greater fool”, allowing them to exit their position.

With the dividend, everyone had their shareholding reduced by 5% whether they liked it or not, so anyone that wanted to maintain the amount they had invested would now need to reinvest their dividend – buying 5% more shares to replenish their portfolio. On the other hand, with the buyback, anyone that wanted to convert 5% of their shareholding to cash could simply have sold 5% of their shares. In both situations, the company has transferred £5 million of cash to its shareholders – the only difference is who had to take an action, and who did not.

There is no difference in value between share repurchases and dividends.

McKinsey & Company

1b. Individual Perspective

We can now imagine two different people, Amy and Ben, each initially with 20 shares. Amy wants to simply hold the shares and watch them grow, while Ben wants an annual 5% cash income from their shareholding. With a stock that pays a dividend, Ben has to do nothing – his 20 shares are now worth £1,900 and he has the £100 of cash he wanted. Amy can use the £100 to buy another share (technically she would need to buy just over 1.05 shares, as the shares now cost £95, but some platforms allow fractional share ownership, so we can gloss over this), to maintain her £2,000 shareholding.

With a share buyback, this time it’s Amy’s turn to do nothing – she doesn’t want to sell her shares, so can keep all 20, which are still worth £100 each. Ben can sell one of his shares to give him the £100 cash, leaving him with a £1,900 investment (this time consisting of 19 shares each worth £100). In fact, Ben doesn’t have to sell his share while the company is implementing their buyback – he can sell his share whenever he wants to. In both scenarios, Amy is left with a £2,000 investment, and Ben has a £1,900 investment and £100 in cash. The exact number and value of the shares isn’t particularly relevant.

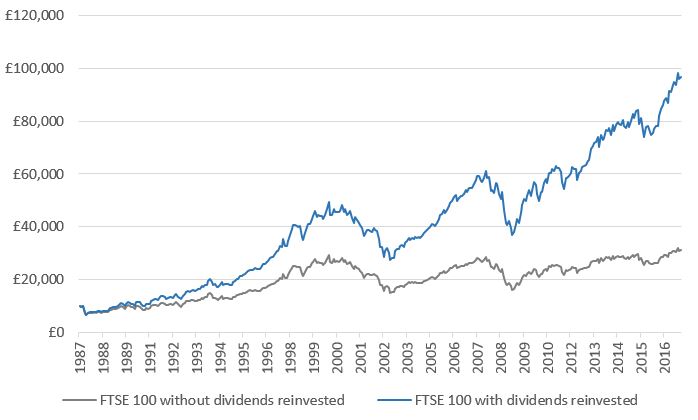

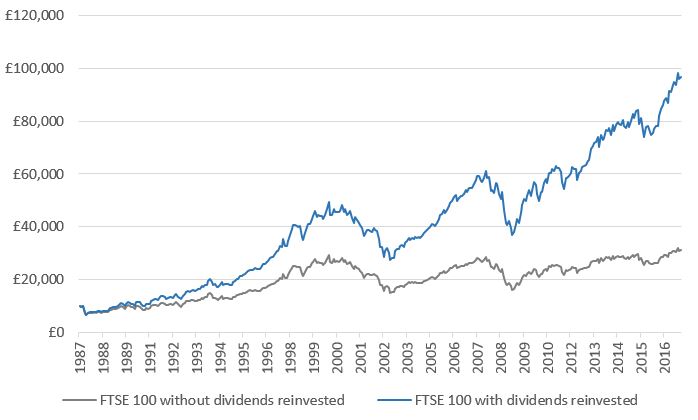

Of course, the difference in the number and value of the shares does affect some things. When a dividend is paid, the share price changes, so a graph of the share price will reflect this movement. This article is a good demonstration of the misleading nature of dividends – just looking at the chart of the share price, you could be forgiven for thinking that Verizon has performed very poorly in comparison with the wider market.

In order to get a true reflection of the actual returns you would have received from such an investment, we need to do some sleuthing to find what dividends were paid, and then some number crunching to calculate the returns with dividends reinvested. Helpfully, many websites do some of this analysis for you, and a “returns with dividends reinvested” option is often available. This isn’t universal though, and doesn’t completely remove the potential for confusion.

The flip side of this, is that with buybacks, a company will slowly be reducing the number of its shares in existence, and if it is remaining a similar size or growing, this means that the individual shares will be getting more and more valuable. Very expensive shares are quite illiquid, as most platforms deal in integer numbers of shares (though as mentioned above, this is slowly changing). The requirement to invest a large minimum amount in a company will put off some investors who don’t have the necessary funds or are unwilling to commit such a large proportion of their net worth.

The solution to this is to perform stock splits – to keep the share price manageable, the company can for example decide to replace their 1 million shares worth £100 with 2 million shares worth £50 each. This is a very common and uncontroversial action, for example since being listed publicly, Microsoft has undergone 9 separate stock splits, and Exxon-Mobil has undergone 5. There is virtually no impact to investors of performing a stock split – you end up with more shares that are worth less, leaving you with the same value of investment. Interestingly it has been a deliberate decision by the board of Berkshire Hathaway to never split their stock, in order to discourage short-term investors, resulting in their share price being around $380,000 in March 2021. If you look at a graph of Microsoft’s share price, the price shown in December 1986 is only $0.17 – this was not actually the case. The price of one of Microsoft’s current shares would have been $0.17, but only because the combination of stock splits since 1987 has split one share into a whopping 288 shares. This means that the price of a single share in Microsoft in 1986 was actually around $49, and if you bought a single share in 1986 for this price, you would now own 288 shares worth over $66,000.

To continue our example of Amy and Ben, we could imagine the company that did a buyback performing a stock split to keep everything even more similar between the two cases. To keep things as similar as possible, the company could do a 20-for-19 split (in which 19 old shares become 20 new shares). This would be unusual, as it would have a fairly minor impact (most splits are 3-for-2, 2-for-1 or higher, for example Apple’s 2014 7-for-1 split), however for the purpose of this example it is informative. The split shares would be worth £95 each, down from £100, and Amy’s 20 shares would become 21.05 shares, while Ben’s 19 shares would become 20. This then perfectly matches the end state where the company paid a dividend instead.

2. Artificial Differences

The fact that the end result of a dividend payment and a share buyback are the same in principle, doesn’t necessarily mean that laws treat them the same. Paying a dividend usually means that the income people receive is taxable – even if they then immediately reinvest it. Equally, selling a few shares will generally incur Capital Gains Tax, so if capital gains are taxed differently to income, receiving a dividend may be more or less tax efficient.

In the UK, this is an unhelpfully complicated thing to consider. Your first £2,000 of dividends and £12,300 of capital gains are tax free, then if you are a basic rate taxpayer dividends are taxed at 7.5% and capital gains at 10%, while if you are a higher rate taxpayer dividends are taxed at 32.5% and capital gains at 20%. This means that depending on your other income, it could be more or less tax efficient for you to have a stock pay a dividend vs. just selling the stock.

Given that the two approaches give the same result from the perspective of the company and the shareholders, in my view the government shouldn’t tax them differently. If a government chooses to treat them differently however, companies can hardly be blamed for picking the one that reduces the tax burden for their investors the most.

Aside from tax, there are also accounting considerations – generally speaking companies are restricted from paying dividends if they don’t have enough profit. It stands to reason that they shouldn’t be paying money back to shareholders, if they haven’t actually made money! Share buybacks are more ad-hoc, and have therefore not yet been regulated to the same extent, leading to some companies borrowing money in order to do a share buyback, despite being loss-making. This is the kind of behaviour that could give buybacks a bad name, so it shouldn’t be a great leap to suggest that similar regulation should be in place to restrict buybacks based on profit.

3. Insider Shenanigans or Just Manufactured Outrage

We are still left with the question of whether buybacks could be used to manipulate the share price of a company. Do share buybacks really funnel money into the pockets of insiders? Of course, if there is any way for people to line their own pockets, you can guarantee that someone will try it – I am not suggesting that there aren’t new and innovative ways for executives to commit securities fraud. I’m simply pointing out that all of the ways that people have so far suggested that buybacks are terrible either don’t hold water, or apply just as easily to dividends too. Let’s run through the popular ones:

EPS manipulation

[This section has been edited since its initial posting.]

This article states that “Buying back shares is a common technique to artificially increase earnings per share”. This is technically true, but not as meaningful as you might think.

Generally, a company must spend its retained earnings in order to perform a buyback. If it is spending its earnings to buy back shares, clearly its total earnings per share can’t increase. EPS however only refers to earnings in the current year, rather than total retained earnings, and it is indeed currently possible for a company to use historic retained earnings to fund a share buyback, without impacting current year earnings. This yields an obvious possible regulatory solution – if people consider this to be a genuine concern, we could simply require that buybacks come out of current year earnings first, before they can use historic retained earnings. This is however not something that I am advocating for – the change in EPS as a result of a buyback is just not that big of an issue.

Companies have to spend cash to purchase the shares; investors, in turn, adjust their valuations to reflect the reductions in both cash and shares. The result, sooner or later, is a canceling out of any earnings-per-share impact. In other words, lower cash earnings divided between fewer shares will produce no net change to earnings per share.

Investopedia – 6 Bad Stock Buyback Scenarios

Once shares have been bought back, of course any future earnings will result in higher earnings per share, because there are fewer shares. This is both obvious, and not a problem – the company’s cost of capital has been reduced, so it is more streamlined, able to provide a higher rate of growth for the remaining capital invested. Why shouldn’t board members get a bonus for reducing costs and increasing the rate of growth?

The EPS concern is therefore mainly with the current year’s earnings to date, however this can be looked at from the same perspective. Had the board decided to do a buyback using historic earnings before the start of the current year, this wouldn’t be an issue, as per the previous paragraph. It is only the fact that they held onto the earnings until later, that causes accusations of foul play. Should executive bonuses be lower if they have been conservative with their cash – waiting until they are confident that they don’t need it before returning it to shareholders? This is a fair question, and one that the company’s Remuneration Committee would want to consider, but looked at from this perspective, it is no longer quite as clear cut as the situation at first seemed.

Executive bonuses are something that a considerable amount of thought goes into. There are entire departments of consultancy firms that exist to advise companies on how to structure executive pay. In most cases, it is simply not the case that the possibility of “EPS manipulation” hasn’t been factored in. It is likely to have been considered in one of a few different ways:

- The possibility of buybacks could already be included in the performance calculations, allowing executives flexibility around buying shares back

- The bonus payments could be calculated based on a “synthetic” EPS basis that remains unaffected by share buybacks

- An irregular or large buyback could trigger a review by the company’s Remuneration Committee, in order to assess whether the existing executive pay structure is fit for purpose

- The executive’s remuneration may not use EPS as a metric at all – there are many other metrics that can be used to more accurately track performance

This compares very naturally with dividends – the other way the company could have disposed of its excess cash. Some companies have executive bonuses that are tied to keeping dividend yields above a certain level – if instead of a buyback, the directors had decided to pay a dividend in order to hit their bonus targets, would we be criticising them? It doesn’t matter – dividends and buybacks do the same thing, so either both are bad, or neither are bad.

Buying back stock options

The same article complains about this in the very next paragraph. Executives and other company employees are often paid bonuses in options (the right to buy shares at a later date at a particular price – the “strike price” of the option). If the share price goes up, these options can be very valuable, as they give people the right to purchase shares at below the market rate, giving them an immediate profit when that right is exercised. It is a true statement, that instead of buying back shares, companies can buy back these options, which is a direct transfer of money to “insiders”, but it is worth considering what the alternatives are.

Let us consider a company that issues 100 options to its employees, each of which confers the right to purchase a share in 1 years time, but at its current market value which is £50. One year later, the share price has risen to £60, so each of these options could be exercised, allowing people to buy a share worth £60 for only £50. At this point, the company could buy the options back for their intrinsic value (£10 each) – this seems to be what the article in question has an issue with, after all, this is a direct transfer of company money to insiders.

The thing is though, the deal is already done – the company has already committed to selling them the shares at a discount, by the nature of entering into an options contract with them a year ago. They can’t just not honour it – that would be fraud. They could of course refuse to buy the options back, and instead force everyone to exercise their option, buying a share for £50, which the employees could then hold on to, or immediately sell for that same £10 profit. But where do these shares come from? The company has to buy a number of shares in order to be able to then sell them on to the option holders. The other side of an option contract that confers the right to buy at a particular price is the obligation to sell at that price, which the company has underwritten.

This therefore isn’t a problem with share buybacks, it is just a natural consequence of a company issuing stock options. If you want to take issue with this mechanism, that’s perfectly fine. The merits and drawbacks of stock options being issued as bonuses makes for an interesting discussion, but that isn’t this discussion.

Overt Buybacks

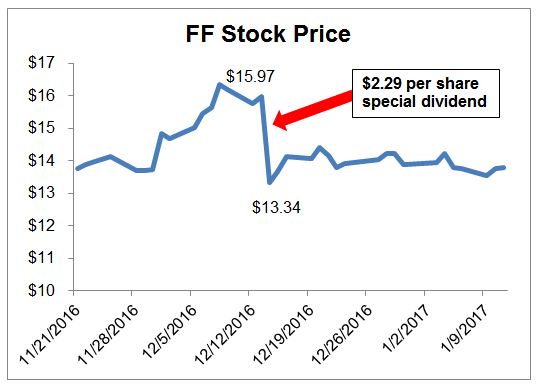

Another article complains that a company announcing a buyback can cause a spike in the price of its shares. This “overt buyback” is seen as a cynical ploy to drive the share price higher, to allow insiders to profit. Well, it is true that sometimes announcing a buyback can cause a company’s share price to rise. This may be due to an expectation that higher demand will drive the share price higher still, or it may be that it triggers greater confidence in the company as it can part with some of its cash reserves, and remain comfortably solvent.

The thing is, this is exactly the same effect you see when a company announces a special dividend. Despite the fact that nothing fundamental has changed about the underlying company, announcing a special dividend generally causes an increase in share price, just like announcing a buyback. Again, if one of these things is bad, then both are. I don’t hear any voices clamouring to ban special dividends, so there’s no reason to single out buybacks as some evil market manipulation tactic either. Of course, as long as we’re being consistent, I don’t mind either way – if people think that both of these are indeed bad, I wouldn’t mind it if special dividends were banned alongside making buyback announcements. Companies would just have to buy their shares back quietly and without fuss. But wait! The same article has a problem with that too…

Covert Buybacks

Ahh, I see – so it’s bad when companies tell you that they’re going to do a buyback, because that causes an increase in the share price, but it’s also bad when companies don’t tell you, because that allows them to buy their own shares more cheaply. Oh the egregiousness of these dastardly executives! Pass the smelling salts!

Seriously though – the company is buying shares from people that want to sell them, at the price that they want to sell them at, whilst at the same time reducing their cost of capital by getting rid of cash they aren’t going to use. Who is losing out here? The sellers aren’t, because they were happy to sell at the market price. The remaining shareholders aren’t, because the value of their shareholding won’t have been significantly impacted, and they now own a slightly higher proportion of the business. This really is manufactured outrage.

Direct Buybacks

Buybacks can also be done a number of ways, and although one way is to do it on the open market, that isn’t always the case. A direct buyback is an agreement to buy shares from particular entities or individuals, who may negotiate the price at which they sell.

By doing a buyback this way, the company sometimes pays a premium above the market price for the shares, which could be seen as unfair to the other shareholders. It can be beneficial to do this when there is low liquidity in the market, as the company can negotiate a price when the market is not reliable at determining the price for such a large order.

As mentioned previously, securities fraud is treated very seriously, so any buyback that overly favoured certain shareholders over others would receive significant scrutiny. That being said, it is not impossible that a direct buyback could be performed inappropriately, overly benefitting an insider with a large shareholding.

With this being the case, open market buybacks are clearly preferable where possible, as they don’t permit such favouritism. It would make sense to be more sceptical of direct buybacks, and the regulation should reflect this.

Excessive Volume or Liquidity Issues

One way that a buyback could legitimately be called manipulation would be if the volume of shares being bought was too large, dwarfing the usual order book, and driving up the price with demand temporarily far outstripping supply. This could easily be managed however, with some very light-touch regulation.

Picking a fairly large and steady company as an example, Costco Wholesale Corporation (COST) has a market capitalisation of $140bn and a share price around $320, meaning they must have around 440 million shares in existence. If they had $7bn of cash sloshing around, that they wanted to give back to shareholders, this would be enough for a 5% dividend (16p per share). Rather than paying a dividend, if they decided to do a share buyback, this would be the equivalent of buying back 22 million shares. This sounds like a lot of shares, but without the need for an ex-dividend date, there is no need for these shares to all be purchased at once. Over the past year, the trading volume has varied between 1m and 8m shares of COST per day – this means that they could spread the buyback over a couple of weeks, and trading would still be within normal parameters.

If share buybacks became the norm, and dividends were relegated to the history books, the somewhat ad-hoc and bespoke nature of buybacks would need to be harmonised and rationalised (in much the way that regulations have done with dividends). Perhaps a daily restriction on the number of shares a company can buy, set at some proportion of the previous day’s trading volume would be appropriate. Also if it became necessary, much like the SEC’s Alternative Uptick Rule for short selling, an equivalent restriction for buybacks could be used. Only allowing a company to buy back stock on a downtick would ensure that a flood of buy orders from the company itself cannot cause a runaway spike in the share price.

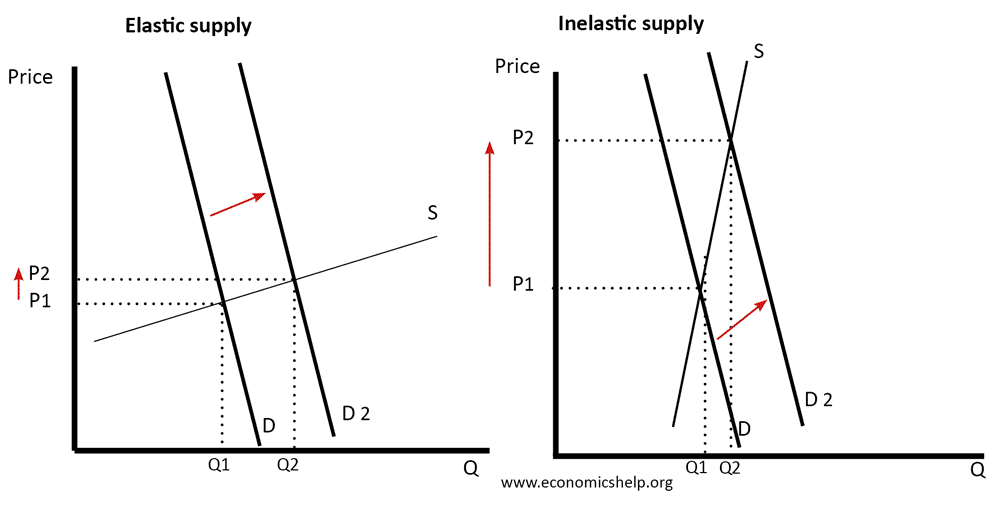

Still though – outside of low-liquidity stocks and situations like a short-squeeze, buybacks don’t really “inflate the share price” because share prices tend to have very elastic supply and demand. The big players in the stock market – market makers, hedge funds and the rest, all have a good idea of what they think the stock is worth, and will buy/sell shares if they think they are under/over priced. This means a very small change in the share price results in a huge demand – try offering to sell a share at the current bid price vs. at the current ask price, and see how fast your orders gets filled! Equivalently, it takes a huge demand to raise the share price a very small amount. Without the implication of market manipulation, the article about Boeing linked at the start of this paragraph could have equally been written about them paying too much in dividends, leaving them in a fragile situation with not enough cash.

4. Don’t Tell Me What To Do

Fundamentally, dividends are a forced action – in receiving a dividend, part of your shareholding is converted to cash whether you like it or not. I am personally of the view that companies shouldn’t be telling investors what to do, or how to manage their money unless they’ve been explicitly asked to.

If someone wants a steady income stream, as pensioners might, for example – they can always sell stocks to generate income. If such people didn’t want to have to actively manage their portfolio, there is no reason that a fund couldn’t act as a wrapper, managing the selling of an appropriate number of shares each month. Not every investor in a company wants to use their investment as an income stream, so why force dividends on all of them? It just results in people having to reinvest their dividends.

The pressure for companies to pay dividends could be harmful too. Irrational though it may be, dividend payments generate excitement for investors, in a way that buybacks do not. The flip-side of this, is that when dividends are expected, the lack of a dividend is disappointing to investors, where the lack of a buyback would not be. A company that regularly pays dividends can find themselves in a position where they would like to invest money in the business, in order to grow the company, but they are strongly discouraged from doing so, as this would require them to “miss” a dividend payment.

Discouraging investment in the future of a company is fundamentally short-termist, and if a company feels that it can’t invest in itself for fear of upsetting its investors, that is a disaster waiting to happen. Far better not to back yourself into a corner in the first place – if no dividends are expected, none can be missed, and investments can be made as needed, without fear of a market backlash.

One final area where dividends just make things more complicated without any discernible benefit is options. As touched upon earlier, options give you the right to buy (or sell) shares at a particular price (the strike price) on a particular date (the expiry date). If you buy a call option on a share currently priced at £100, with a strike price of £105 and an expiry date one year from now, this will give you the right to buy a share for the price of £105 in one year’s time, regardless of what its price actually is. If the shares have increased to £110, you will be able to buy them for £105 and sell them at £110 for an immediate £5 profit, while if they have only increased to £105 or less, your option will expire worthless as there would be no benefit in buying the share at above the market price.

If you bought this option, and the share price of the company has increased to £110 over the last year, you might think you’re going to be making a profit, but what if the company pays a £5 dividend before you exercise your option? Once the ex-dividend date is reached, the share price drops by about £5, leaving your option worthless. If a share buyback had been done instead, there would have been no direct impact on the share price, leaving the option’s gain largely intact. Of course, if you are aware of the risk, there are strategies to manage it, but this is just another thing you have to think about.

Conclusion

If you want a nice consistent cash payment, buy bonds instead. Stocks are all about capital growth, and dividends obscure that. In an ideal world, dividends would just be phased out in favour of share buybacks – they aren’t worth the hassle or the hype. If you’re still not convinced, check out this video by InTheMoney, who expresses the point very succinctly.